We are fortunate to be involved in an industry where superyacht owners and their designers are free to express themselves in the most extraordinary ways, by building cutting edge, iconic, ocean going masterpieces, the complexity and detail of which is breathtaking. However, one wonders if sufficient attention is given to the human element and occupational safety and health (OSH) in the design process?

Whilst there has been significant focus and improvement in safety within the shipping industry, and I include yachts within this group, accidents and incidents are still occurring, sometimes with devastating consequences. And, whilst most research would suggest that ‘human error’ is a major factor, one third of all marine accidents have also been associated with poor design (Grech et al., 2008 – Human Factors in the Maritime Domain).

Today there is greater emphasis being placed on human factors and ergonomics in ship design and there are already initiatives such as the CyClaDes project that are working to improve OSH. This is essentially a crew-centered approach, where the working processes, hazards and risks are considered by all the stakeholders involved in ship design and operation, and where design is used as part of the methodology to optimize working efficiencies and remove or minimize hazards and risks.

There are already numerous Conventions, Codes and Guidelines, relating to technical aspects of yacht design, construction and equipment, but unfortunately very little when it comes to the human factors and ergonomics.

An example of the technical bias is that, following an incident the UK Maritime and Coastguard Agency (MCA) introduced MGN 422 – Use of Equipment to Undertake Work Over the Side on Yachts and Other Vessels. This details the technical standards, which is good thing, but does not make any recommendations about the number or location of tracks required in respect of the routine task of cleaning and maintaining a yacht. We know that designers are loath to spoil the lines of yachts by placing tracks along the ships side, which raises the question; do aesthetics take precedence over safety?

The Maritime Labour Convention 2006 (MLC) provides some guidance, in particular the following suggests that design should play a part: –

MLC 2006 Guideline B4.3.1

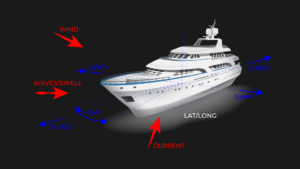

3. The assessment of risks and reduction of exposure on the matters referred to in paragraph 2 of this Guideline should take account of the physical occupational health effects, including manual handling of loads, noise and vibration, the chemical and biological occupational health effects, the mental occupational health effects, the physical and mental health effects of fatigue, and occupational accidents. The necessary measures should take due account of the preventive principle according to which, among other things, combating risk at the source, adapting work to the individual, especially as regards the design of workplaces, and replacing the dangerous by the non-dangerous, or the less dangerous, have precedence over personal protective equipment for seafarers.

The ILO Guidelines for Implementing the OSH Provisions of the MLC 2006 offers further guidance on ‘Preventative Principles’.

So, although there are some resources available, it is very much open to interpretation, which means we have to rely on the mindset and the experience and understanding of those involved to ensure work place safety is given the importance it deserves.

I suspect part of the problem is that designers may not have the relevant practical knowledge, something perhaps alluded to recently by Carlo Nuvolari, of Nuvolari Lenard, when he states in an interview in Boat International – Nuvolari Lenard discuss the problem with yacht design 18 November 2015 by Stewart Campbell:

“A lot – not all, but a lot – of our colleagues don’t go on boats. I can’t understand it.”

I would go further to suggest that this observation also applies to many of the others involved in the superyacht industry, such as: naval architects, shipyards own design/technical departments, flag and the owners representatives who are often the party responsible for signing off drawings in a full custom build.

There is no doubt that OSH is a huge and important subject that covers all aspects of life and work on board and affects all crew, and all departments; interior, catering, engineering and deck. Deck crew, for example, perform many routine tasks that involve some element of hazard and risk, including: working aloft, over-side, launching/recovering tenders and toys, anchoring and mooring operations, where the design of equipment, fittings, equipment and layout will have an impact their ability to carry out their tasks safely and efficiently.

In recent years we have seen the growth in the popularity of the enclosed foredeck. They add an elegance to the fore part of a yacht, and also offer the capability of a touch and go heli-pad. However, there are issues with safety due to the enclosed space and what can be a compromised layout; as a secondary consequence, they can have an impact on crew welfare by removing the only exterior space where crew could get fresh air and sun.

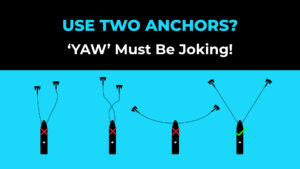

When I first saw the Cayman Island Shipping Registry (CISR) Flyer To The Shipping and Yachting Industry, available here, relating to the tragic incident on Ocean Victory, the first thing that struck me was the mooring arrangement; with the windlass/capstan positioned between the operator and the means of ingress/egress from the mooring space. And, whilst I am not suggesting this was a contributory factor – we need to wait for the full report to know more – I feel it does raise a more general question about this kind of layout and operator safety. This was also raised in an IHS Fairplay article relating to the incident:

“He also said the layout of the mooring deck on Ocean Victory should be examined, as it appeared that there was nowhere for those operating the anchors to take shelter in case of a brake failing. For this, the flag state is ultimately responsible, Graveson concluded. ( IHS Seafarer death on luxury yacht prompts investigation – 29 May 2016)”

In addition, there does appear to be a contradiction with the of Code of Safe Working Practices for Merchant Seafarers (CoSWP) 26.2.1 “…During anchoring, they should stand aft of the windlass/capstan” and this type of layout.

From my perspective I find it hard to see how this arrangement is inherently safe without suitable protection and/or clear escape routes for the crew, or alternative means of operating the windlass such as remote operation by hydraulic brake? At least Ocean Victory seems to have clear, clean working spaces around the windlass/capstan and bitts; there are other examples where this is not the case as we will see later.

As there was a question of responsibility I thought it worthwhile to look at the legislation that affects anchoring and mooring.

SOLAS II-I 3-8

2. Ships shall be provided with arrangements, equipment and fittings of sufficient safe working load to enable the safe conduct of all towing and mooring operations associated with the normal operation of the ship.

This is further detailed in Guidance on shipboard towing and mooring equipment (MSC/Circ.1175).

As allowed by SOLAS, responsibility for ensuring compliance is normally delegated to a Recognised Organistaion (RO) i.e. one of the members of the International Association of Classification Societies (IACS) who have rules on Mooring, Anchoring and Towing.

Importantly however, these rules only deal with the technical aspects of size and strength of the equipment and fittings based on the vessels calculated Equipment Number (EN) – there are no rules on the layout.

Ultimately then, the responsibility for ensuring safe working within this space resides with the flag, owner/operator, master and crew via the various codes and conventions such as International Safety Management (ISM) Maritime Labour Convention 2006 (MLC 2006) and MCA Code of Safe Working Practices (CoSWP) or whatever occupational health and safety legislation other administrations have in place.

As mentioned, I have seen worse examples of this style of foredeck and on one vessel I saw a whole catalogue of issues relating to the safety, including: –

- Small radii on fairleads, increasing point loads and possibility of lines breaking

- Bitts too close to fairleads/ships side – not enough space for crew to work and poor leads when stoppering lines, resulting in jammed or broken stoppers

- Multiple obstructions such as hatches, rescue boat and crane, severely restricting movement, working space and escape in the event of runaway chain

- Windlass/capstan operator standing forward of windlass/capstan

- Entrance/exit to foredeck aft of the windlass/capstan – no safe escape

- Noise – the enclosed space was nosier and communication more difficult

- Snap Back Zones – the confined layout meant whole space was a ‘potential snap back zone’ including the drop down observation bulwarks

- There is no doubt that many of these hazards could have been eliminated if better consideration had been given to the practical aspects of working of the space and associated risks.

With reference to ‘snap back zones’ there is an excellent guide from Seahealth Denmark entitled MOORING – DO IT SAFELY, that I highly recommend. The following excerpt certainly makes you think!

“The killing force of a broken line – The area travelled by a parted line with enough force to kill someone on its way is known as the snap back zone. If any line parts with a bang, then its broken ends are moving faster than 690 knots which is the speed of sound in air.”

Incidentally, how many crew wear the full Personal Protection Equipment (PPE) including safety helmets, as recommended by CoSWP, during mooring and anchoring operations?

Similar issues can also be observed on open foredecks e.g. on one previous command the deck crew had to climb outside the bulwark to sight the anchor and chain during anchoring operations – clearly not the safest, or most practical solution, to what is a fundamental task.

The loss of anchor and chain is not an uncommon occurrence in the maritime industry, whether due to equipment failure, poor maintenance, or human error; fortunately there have not been a significant number of injuries or fatalities due to this. This is not true of mooring failures where injury and fatality is a more common occurrence, and as yachts get bigger, and loads increase, there is far greater potential for serious injury if something goes wrong – I don’t think this is always well understood.

As an industry I think we are perhaps failing to share knowledge and experience of accidents, incidents and near misses due to confidentiality, reputational damage, etc., something I raised at the Global Superyacht Forum (GSF) last year. I am not sure how this could be improved given the conflicting interests, but I firmly believe, like other industries, learning from these incidents can make a significant difference to the safety of yachts and crew.

The crew play a significant role in safety through risk assessments, working practices, crew training, effective communication and leadership, and crucially through a strong safety culture – the organizational and cognitive aspects of occupational safety. However, there can be no doubt that safety can also be improved through design, and that safety should be a priority whenever there is human interaction with hazards and the risk of damage and/or injury involved.

For our industry this is clearly a challenging task given the conflicting demands of yacht design and use, the variability of yacht platforms, ownership cycle, equipment, working practices and the quality and competency of crew, but one we should rise to.

The IMO have recognized the importance of the human element in Resolution A.947(23) in 2003 – Human Element Vision, Principles and Goals for the Organization. One of those principles is as follows:

a) The human element is a complex multi-dimensional issue that affects maritime safety, security and marine environmental protection. It involves the entire spectrum of human, activities performed by ships. Crews, shore-based management, regulatory bodies, recognized organizations, shipyards, legislators, and other relevant parties, all of whom need to co-operate to address human element issues effectively.

I believe as an industry we can apply those principles, and can make improvements in safety and working arrangements through design; recognising that it is an iterative process and requires a holistic approach that is enabled through better sharing of practical knowledge and experience and improved collaboration between all stakeholders.